International Relations

Speeches

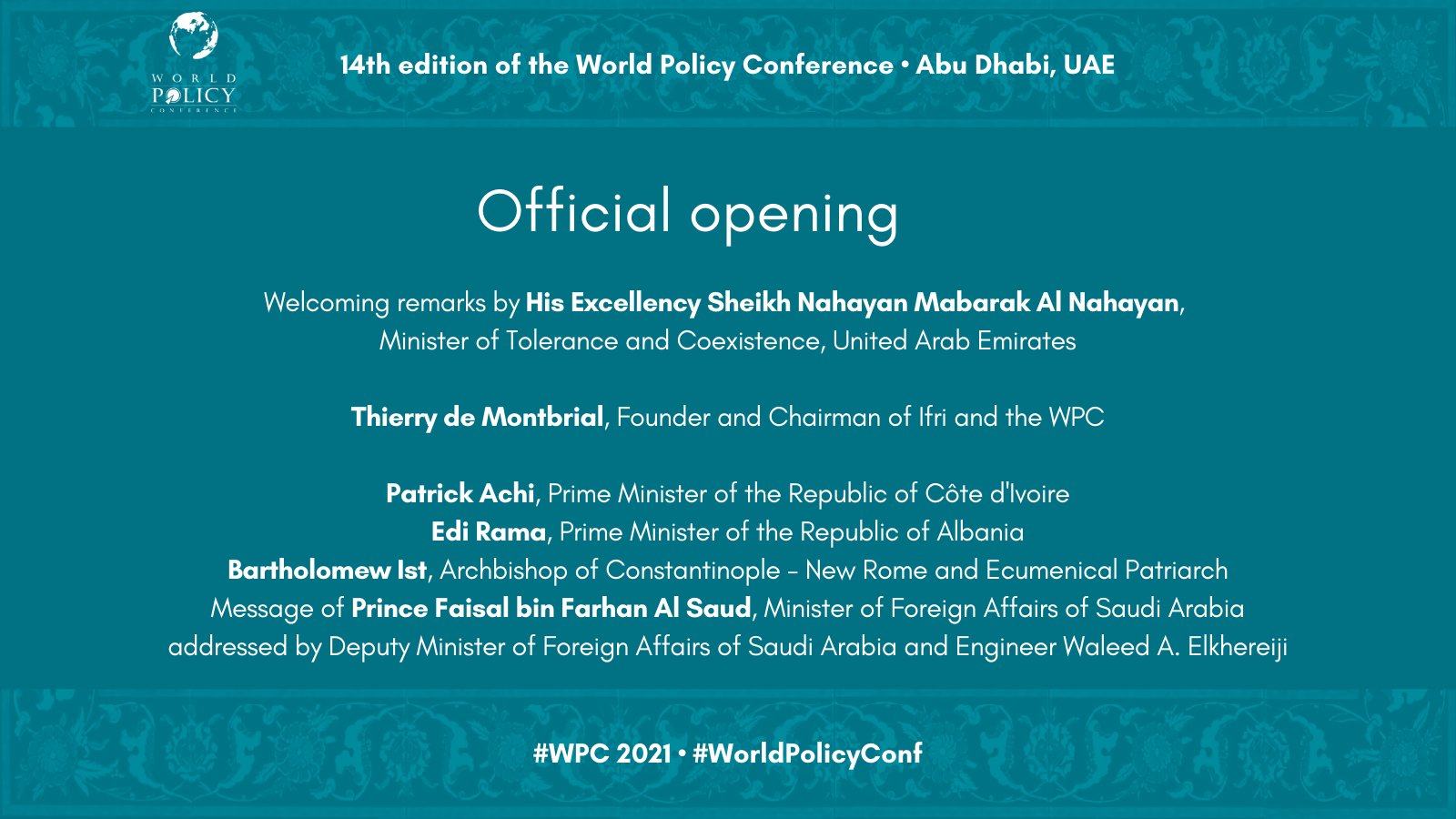

Abu Dhabi, October 1, 2021

I am particularly happy that the fourteenth World Policy Conference is taking place in Abu Dhabi nearly two years after the twelfth in Marrakech. The absence of a thirteenth edition in the WPC timeline—like buildings in the United States without a thirteenth-floor elevator stop or planes without a thirteenth row—will always mark the year 2020, which will stand out in the history of the contemporary world.

The shock of September 11, 2001; the 2007-2008 subprime crisis and its aftermath; the very poorly named “Arab Spring” early in the following decade; the Covid-19 pandemic; and of course climate change, whose effects are now being felt in the everyday lives of people around the world, are some of the early 21st century events that recall the fragility of the human condition in both its collective and individual dimensions.

Geopolitically, the thaw in the international system since the fall of the Soviet Union, combined with the meteoric rise of China, whose ambitions are increasingly clear, remind those who dreamed of a blissful age of globalization that the flat world of its ideologues was an illusion. In some respects, today’s world resembles that of the early 20th century, when the lack of any sort of global governance, to use a contemporary term, led to the First World War.

The pandemic (whose outcome is still very uncertain) has accelerated technological and social transformations already well underway, while the sudden hardening of the Sino-American rivalry has intensified changes in the world and the ensuing uncertainties. Many observers, even well-informed ones, have not seen or wanted to see that Joe Biden’s election would not change the course of US foreign policy, which now focuses entirely on China. Biden’s style is certainly more traditional than his predecessor’s, but his actions are no less abrupt and unilateral. Hopes for a return to multilateralism, or at least consultation between allies in bodies like NATO, have faded. The conditions in which American forces were withdrawn from Afghanistan and the announcement of a new alliance between Australia, Great Britain and the United States (AUKUS) are two recent examples. They are unlikely to be the last.

If States like Japan and South Korea have reason to believe that they are safe from Washington’s about-faces, it is because US interests are very important there. Many other countries feel the need to brace themselves for profound reconfigurations or even regional conflicts in which the United States would only be marginally interested. Like nature, geopolitics abhors a vacuum. This was recently seen in the Middle East under Trump’s presidency, when Russia and Turkey flexed their muscles. Confrontations on a more or less large scale are likely wherever the interests of the United States or China are not directly at stake. Where they are, as in Taiwan, head-on collisions are inevitable in the next few years unless the new world’s two superpowers establish a dialogue comparable to the one the United States and the Soviet Union set up after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Perhaps it would take a crisis of similar magnitude to get there.

Another source of concern is the growing politicization of the economy and finance, notably through sanctions. Until now, this has mainly been an American weapon, but China can be expected to methodically resort to them. More broadly, each of the two rival superpowers intends to develop its own globalized system, which would result in two competing spheres in cyberspace and new forms of dividing the world up into zones of influence.

However, most countries do not want to find themselves having to pick sides and, thereby, becoming vassal States. This is especially true of the European Union in general and its component parts in particular. Of course, Europeans have a major interest in preserving freedom of navigation in the area now known as the Indo-Pacific, and they unreservedly contribute to this. They attach great importance to deepening their relations of all kinds with India, Japan and South Korea. Naturally, the European Union’s member States feel culturally and, therefore, politically much closer to the United States than to China. Europeans cannot show themselves to be “equidistant” and they say it. And yet, their interests with regard to Asia in general and China in particular do not exactly coincide with those of the United States—far from it. They could not accept an imposed transformation—pitched as preventive—of the Atlantic Alliance into a de facto American organization aimed against China. Their main immediate security interest have more to do with their neighbors’ instability.

It would make good economic, political and geostrategic sense for Europeans to collectively structure their ties to their southern neighbors, the Middle East, Africa and, naturally, Eastern Europe, including—and I stress this point—Russia. All of us should focus our efforts mainly on relationships with our neighbors to boost the chances of harmonious economic and social co-development while giving ourselves the most autonomous means possible to build the collective security of this vast region, whose peoples are destined by history and geography to live together.

This of course does not mean working against the United States, but nor do we want a confrontation with China beyond what preserving our essential interests requires, for example in the area of technological sovereignty.

That said, there is a pre-condition for keeping the global peace in the coming decades: an understanding between the United States and China based not on a sort of division of the world but, on the contrary, on what can be called humanity’s common interests, starting with health and the climate, as we are now discovering or rediscovering. If this condition goes unmet, other States will be unable to successfully meet the tremendous challenges the world can be expected to face in these areas in the coming decades. With a bit of optimism, strong cooperation between the two superpowers on humanity’s common good could hopefully extend to other issues.

These few thoughts are not meant to be pessimistic, but lucid. More than ever, I believe in the WPC’s calling as it has been defined since its inception in 2008: medium-sized powers must work together to put across their views on the conditions required to keep the world reasonably open, i.e. globalization without hegemony or any form of extremism. It seems to me that this idea is shared by the United Arab Emirates, which is hosting us today at the very time when the Dubai World Expo is opening, whose symbol is precisely balanced globalization through the smart, reasonable use of technological resources.

The entire Middle East is suffering, but the region potentially has everything it takes to again become a place of hope and prosperity. Moreover, everyone has become aware of Africa’s immense resources. Europe, if it manages to surmount the challenges inherent to its integration, could become even more of what it has been in past decades, i.e. a pole of prosperity, freedom and peace that has renounced all forms of imperialism.

It is clear that in a world of shrinking distances, Europe in the broad sense, the Middle East and Africa form a community of destinies.

Conversation with Charles Michel, Former President of the European Council

09 September 2025

Opening Remarks of the 17th edition de la World Policy Conference

13 December 2024

17h edition of the World Policy Conference

10 December 2024

Opening Remarks of the 16th edition of the World Policy Conference

03 November 2023